The game's central mechanic is construction under constraint. You get four random digits and must build a mixed fraction using three of them—one for the whole number, one for the numerator, one for the denominator. The constraint: numerator must be ≤ denominator. So with digits 2, 5, 7, 8, you could make 7⅝ or 5⅞ or 2⅞, but not 8⁷⁄₅. This forces students to think about what makes a valid fraction before they start computing.

Here's where it gets interesting mathematically. That constraint means students have to estimate magnitude on the fly. Is 7⅝ bigger than 5⅞? Well, 7⅝ is about 7.6 and 5⅞ is about 5.9, so yes. But notice that ⅞ is larger than ⅝ as a fraction, even though 5⅞ is smaller as a mixed number. Students start developing intuition about how the whole number and fractional parts contribute differently to overall size.

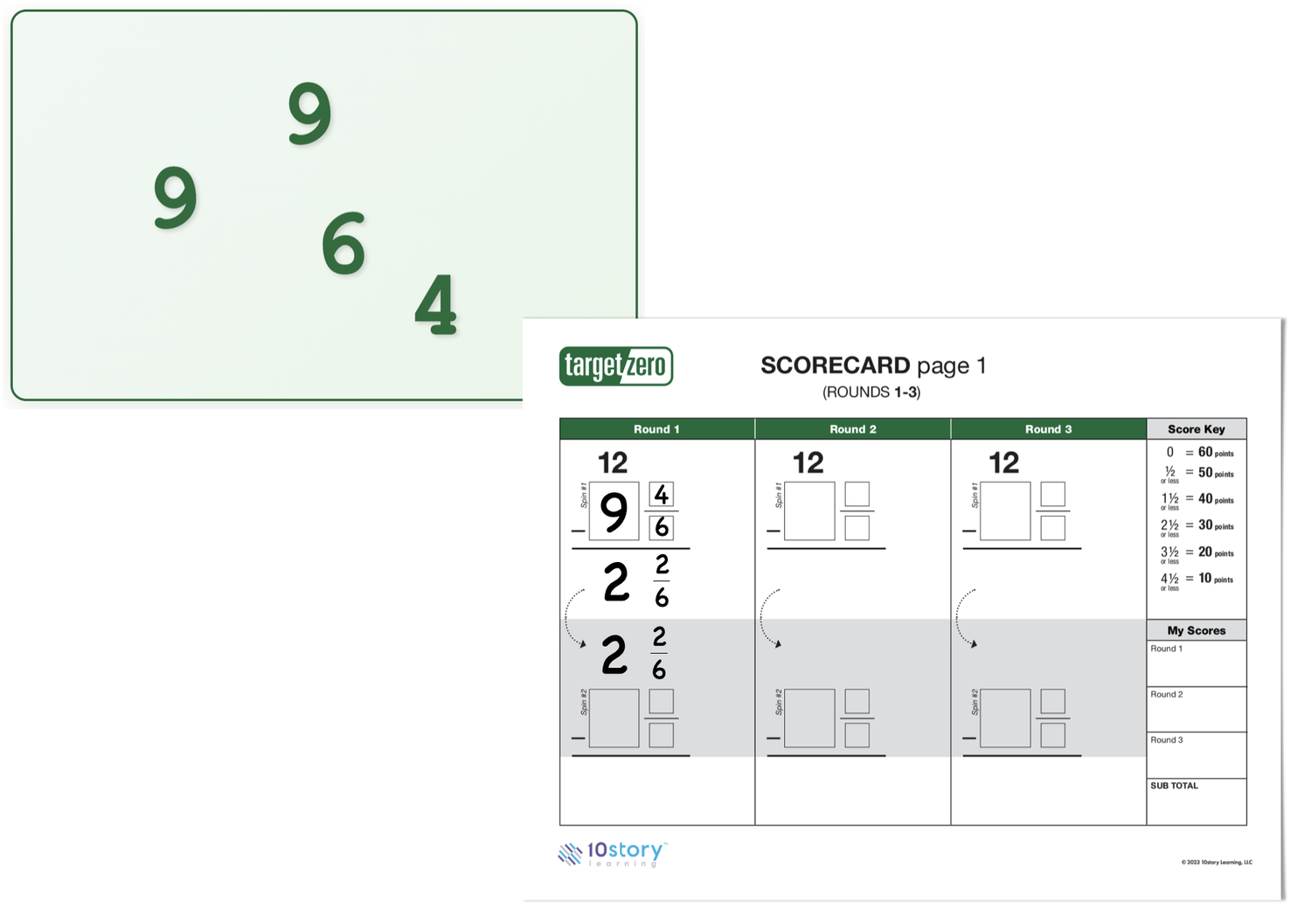

The subtraction happens in two stages. First, subtract your mixed fraction from 12. This often requires regrouping—if you're subtracting 8⅚ from 12, you need to rewrite 12 as 11⁶⁄₆ to handle the fractional part. Then you subtract a second mixed fraction from whatever you landed on. This two-step structure means students practice both "whole number minus mixed fraction" and "mixed fraction minus mixed fraction" in every round.

Common denominators come up constantly. If your first subtraction lands you at 3¾ and you need to subtract 1⅖, you're finding a common denominator for fourths and fifths. That's twentieths: 3¾ becomes 3¹⁵⁄₂₀, and 1⅖ becomes 1⁸⁄₂₀, giving you 1⁷⁄₂₀. Students who play regularly get fast at finding common denominators for the digit combinations that appear frequently.

The scoring system rewards precision but forgives near-misses: Landing exactly on zero gets you 60 points. But ½ gets you 50, and 1 gets you 40. This means you don't need perfect computation to score well—you need good estimation. Students learn to aim for the neighborhood of zero rather than obsessing over exact calculations.

Strategic play requires thinking ahead. If you make 8⅚ on your first draw, you'll subtract from 12 to get 3⅙. Now you need your second fraction to be as close to 3⅙ as possible. But you don't know what digits you'll get. Good players start developing a sense of which first-move fractions leave them flexible for the second subtraction. Sometimes making 6½ instead of 8⅚ gives you more options later.

The game naturally includes improper fractions and mixed number conversions. If a student lands on 1⁷⁄₅ after their first subtraction, they might convert it to 2⅖ before attempting the second subtraction. This back-and-forth between representations isn't explicitly taught—it emerges from students trying to make the computation easier.

What makes this pedagogically useful is the estimation-before-computation pattern. Students who jump straight to calculating often make errors and end up far from zero. Students who pause to estimate—"This should land me around 3, then subtracting about 2½ should get me close to ½"—tend to catch computational mistakes and score better. The game rewards the habit of checking whether your answer makes sense.