Students often memorize that 100 cm = 1 m without developing any intuitive sense of what this means in physical space. On the Spot addresses this through repeated cycles of measurement and conversion in a context where the numbers actually matter—they determine your score.

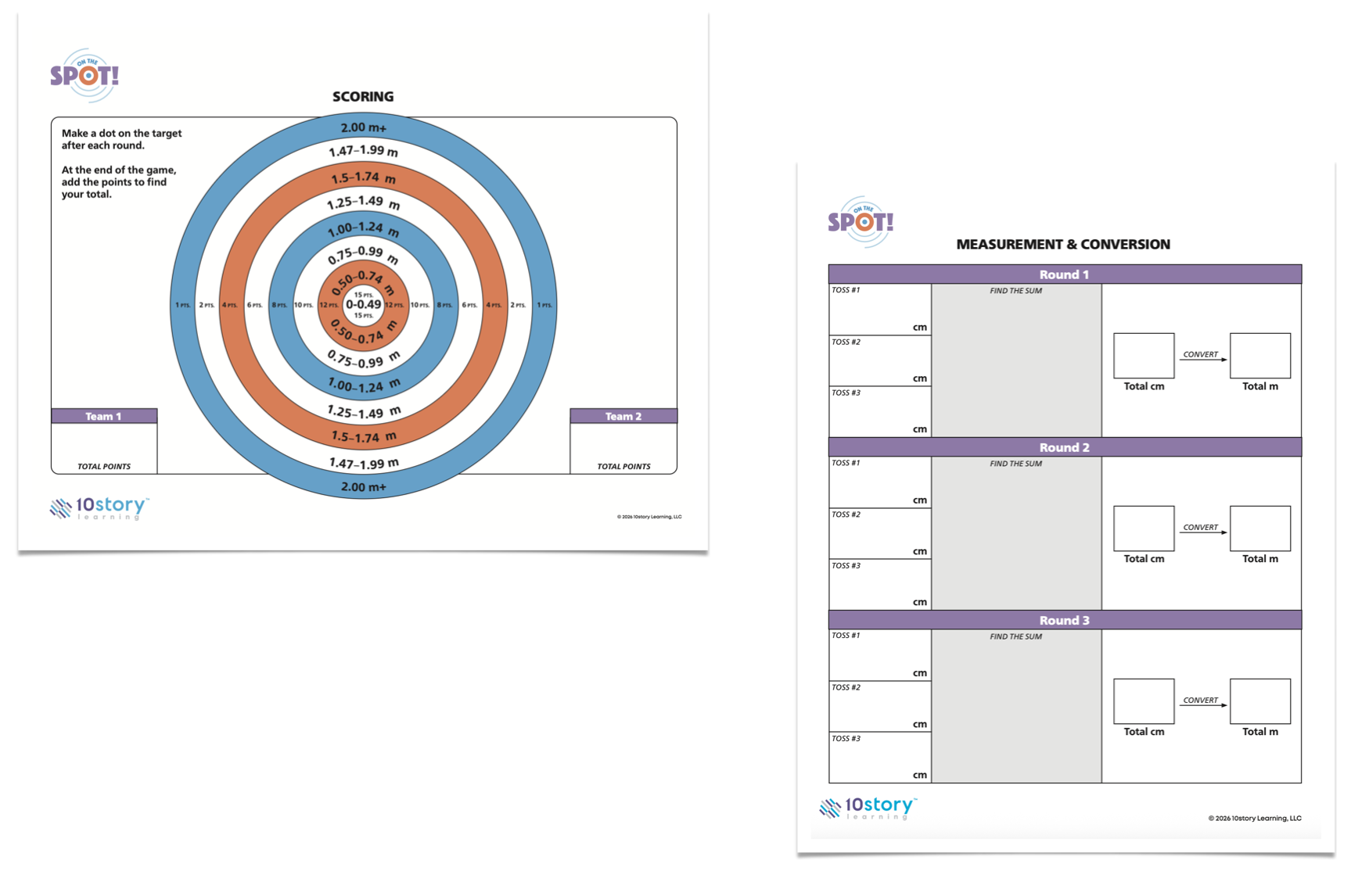

The game structure is straightforward: toss a beanbag, measure how far it landed from the target in centimeters, record the distance. Do this three times, add up the centimeters, convert the sum to meters, and plot your score on a target board. The team with the most points after three rounds wins.

Repetition with variation builds fluency: same conversion relationship, different measurements each round.

Each round gives students three distinct mathematical tasks. First, they measure with a ruler. This sounds simple, but accurate measurement requires aligning the ruler correctly, reading at the right edge, and recording precisely. Students get immediate feedback—a careless measurement means an incorrect score.

Second, they add three two-digit or three-digit numbers. This happens in the context of measurement rather than isolated arithmetic. If your tosses land at 67 cm, 39 cm, and 94 cm, you need that sum to know your score. The addition serves a purpose beyond getting the answer right.

Converting 200 cm to 2.00 m requires understanding what division by 100 does. Students practice this conversion three times per game, building automaticity with the procedure while seeing how different centimeter totals map to different meter values.

The scoring system reinforces relative magnitude. The target shows meter ranges: 0–0.49 m scores the most points, 0.50–0.74 m scores less, and so on out to 2.00 m+. Students see that 50 centimeters is a meaningful distance—it's the cutoff between maximum points and good points. This visualization grounds abstract meter values in physical space.

The place value work here is subtle but important. When students convert 147 cm to 1.47 m, they're not just moving a decimal point—they're seeing that the same quantity can be expressed at different scales. The 1 represents one whole meter, the 4 represents 40 centimeters (four-tenths of a meter), the 7 represents 7 centimeters (seven-hundredths). The digits stay in proportion; the decimal point shifts.

Physical measurement makes unit relationships concrete rather than abstract.

Estimation develops naturally. After a few rounds, students start predicting before measuring: "That looks like about a meter" or "Maybe 75 centimeters?" They check their estimates against actual measurements, refining their intuition about metric distances. This is harder than it sounds—most adults struggle to estimate in metric units because they lack this kind of repeated, grounded practice.

The team structure means students see multiple examples each round. While one person measures, teammates can verify the reading. When converting, everyone can check the decimal placement. This collaborative verification catches errors and builds confidence with the procedures.

The game also distinguishes between precision and accuracy. A measurement can be precise (carefully read to the nearest centimeter) even if the throw wasn't accurate (landed far from target). This distinction matters in science and engineering, and students encounter it here through gameplay rather than lecture.