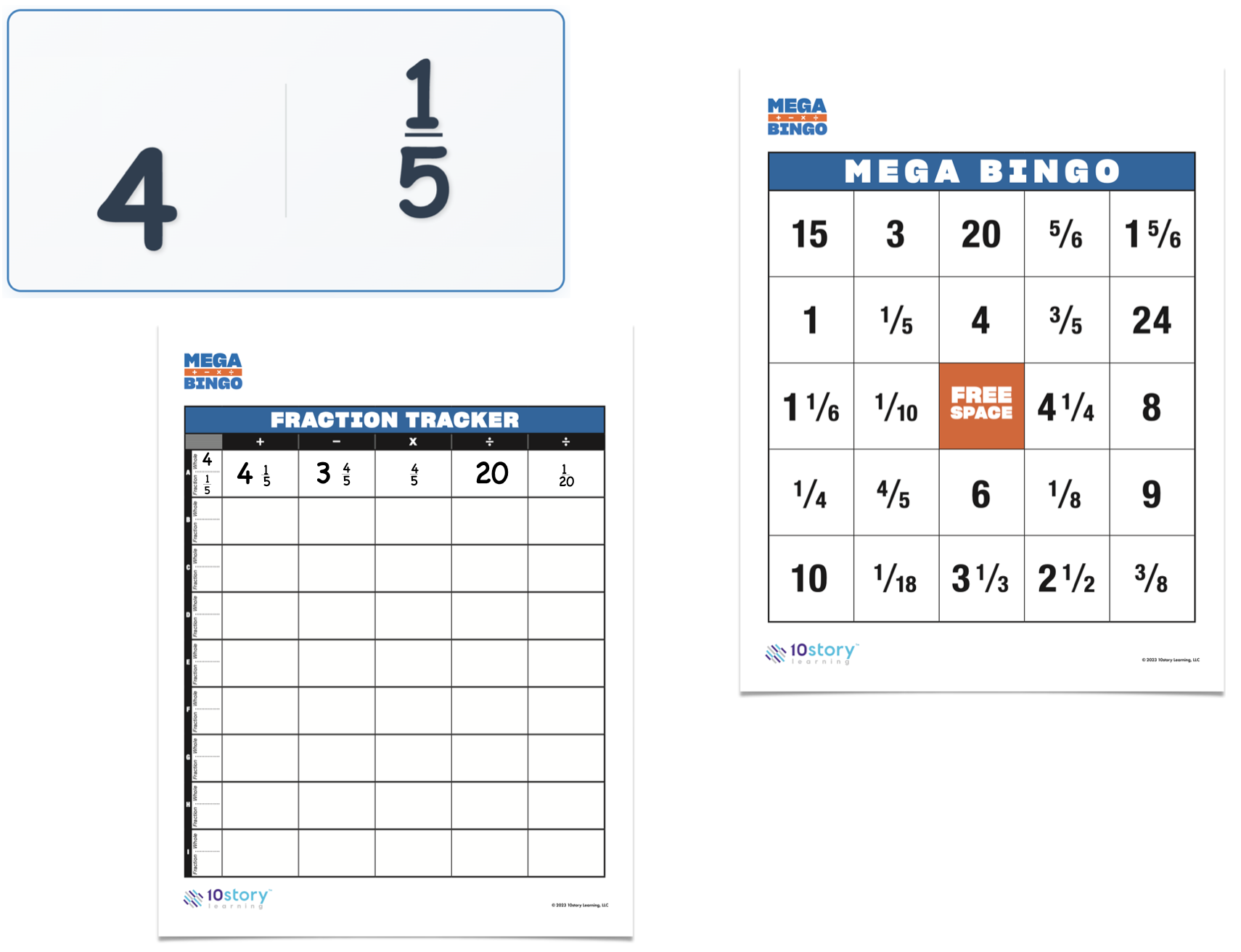

Most fraction curricula teach operations in isolation: a unit on addition, another on multiplication, separate lessons for each type of division. Mega Bingo does the opposite—students compute all five operations on the same pair of numbers, round after round. When the generator produces 4 and ½, teams calculate 4 + ½ = 4½, 4 - ½ = 3½, 4 × ½ = 2, 4 ÷ ½ = 8, and ½ ÷ 4 = ⅛. Same inputs, wildly different outputs depending on the operation.

This systematic approach does two things at once. First, it builds procedural fluency through distributed practice—over a game, students might perform 75-100 calculations across all five operations. Second, it makes operational relationships visible. Students see that multiplication and division produce more dramatic changes than addition and subtraction, that dividing by a fraction yields larger results while dividing a fraction yields smaller ones, that the two division operations create reciprocal relationships.

The same two numbers, five different operations, five different meanings.

Each operation has distinct conceptual grounding. Addition combines (4 and ½ together), subtraction removes (4 minus ½), multiplication scales (4 groups of ½), division by a fraction partitions (how many halves in 4?), and division of a fraction by a whole splits (½ divided into 4 parts). These meanings map onto different computational procedures: common denominators for addition and subtraction, multiply across for multiplication, invert-and-multiply for fraction division, multiply denominator for division by a whole.

The strategic layer matters pedagogically. Students choose which of their five computed results to place on the board, considering which spaces advance their bingo pattern. This decision-making keeps engagement high—you're not just computing for its own sake, you're computing to win. And when a team calls bingo, they must verify their calculations to the room, creating natural opportunities for mathematical discourse and error correction.

Students record both starting numbers, then systematically compute and document all five results in columns. This written record serves three purposes—it organizes work during play, provides evidence for verification, and creates an artifact teachers can review to see where students struggle.

Difficulty differentiates naturally through random generation. Some rounds produce easy pairs (3 and ¼), others produce more complex calculations (15 and ⅝). The game accommodates a range of fluency levels without feeling like obvious differentiation, since every team works with the same numbers each round but at their own computational pace.

The collaborative structure lets students distribute cognitive load. Teams can split operations—one student handles addition and subtraction, another tackles the divisions—then check each other's work. This division of labor keeps wait time low while maintaining individual accountability, since every student must understand enough to verify their teammates' calculations.