GeoDraw addresses a fundamental challenge in geometry education: students often learn **geometric terminology** in isolation from **visual recognition** and application. The game creates a context where students must both **produce geometric elements** deliberately and **identify them within complex compositions**—mirroring how geometric concepts appear in architecture, design, and the physical world.

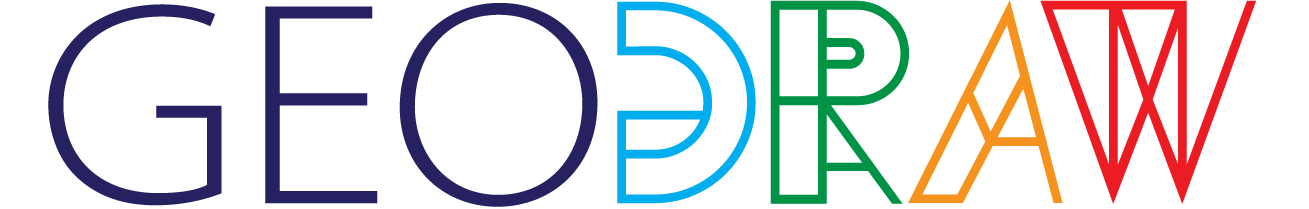

The structure requires students to work with geometric elements in **three distinct cognitive modes**. First, they must draw specified elements—**translating formal definitions into precise visual representations**. A student who receives "acute angle" must recall that this means an angle measuring less than 90 degrees, then create that configuration. This production phase demands understanding of **defining properties**.

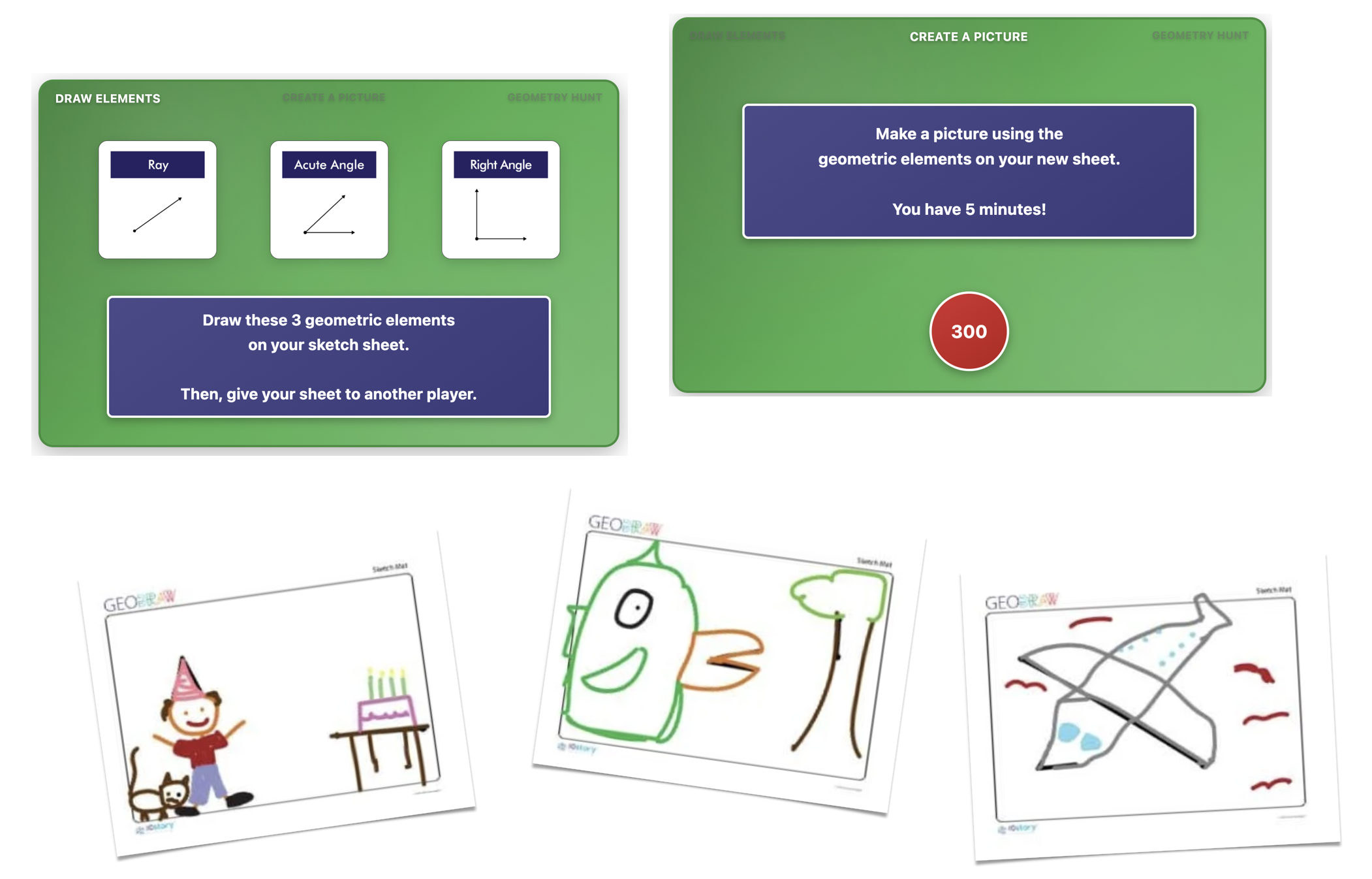

Second, students must **incorporate formal geometric elements into creative artwork**. When a student transforms a line segment into the edge of a building, or an acute angle into the prow of a ship, they're recognizing that geometric elements aren't just abstract objects but **foundational components of visual representation**. This integration challenges students to see **mathematical structures as building blocks**.

Third, students must **identify geometric elements within another student's artwork**. This visual search requires **recognizing familiar forms in unfamiliar contexts**. The acute angle that one student deliberately drew might appear as part of a tree, a roof, or a stylized letter. Students develop facility with **abstracting formal properties** from visual complexity—an essential geometric skill.

Students discover that their classmates' drawings contain far more geometric elements than the original three assigned. Lines become edges, vertices create angles, shapes emerge from intersecting elements.

The game works with **fundamental geometric vocabulary**: points, line segments, rays, lines (infinite in both directions), and angle types (acute, obtuse, right, straight). Students must distinguish between related but distinct concepts. A line segment has two endpoints; a ray has one endpoint and extends infinitely; a line extends infinitely in both directions. These **distinctions matter** when identifying elements in drawings.

Angle classification requires students to **estimate angle measures visually**. An acute angle looks noticeably "sharp," opening less than a right angle. An obtuse angle appears "wider," opening more than 90 degrees but less than 180. Students develop **intuition about angle magnitude** through repeated practice identifying and classifying angles in varied orientations.

The game introduces **relationships between geometric elements**: parallel lines (never intersecting, always the same distance apart), perpendicular lines (intersecting at right angles), and intersecting lines (meeting at any angle). When students identify these relationships within drawings, they're recognizing **geometric properties that remain invariant** despite changes in orientation, scale, or artistic context.

Two-dimensional shapes emerge naturally as students create drawings. A triangle contains three line segments and three angles; a quadrilateral has four sides and four angles. Students begin recognizing that **shapes are defined by their geometric components**—sides, angles, vertices—and that these components can be identified even when embedded in complex images.

The collaborative nature means students see **multiple interpretations of the same requirements**. Given the same three elements, different students create vastly different artwork, yet all contain the specified geometric structures. This variation demonstrates that **geometric properties exist independently** of specific visual representations.