Coordinate planes are everywhere: GPS navigation, computer screens, flight paths, city grids. The abstraction—representing two-dimensional position as an ordered number pair—underlies everything from video game programming to epidemiology mapping. But students often encounter coordinates as notation to memorize rather than as a representational tool that solves real spatial problems. 4Square turns coordinate plotting into strategic decision-making under constraint.

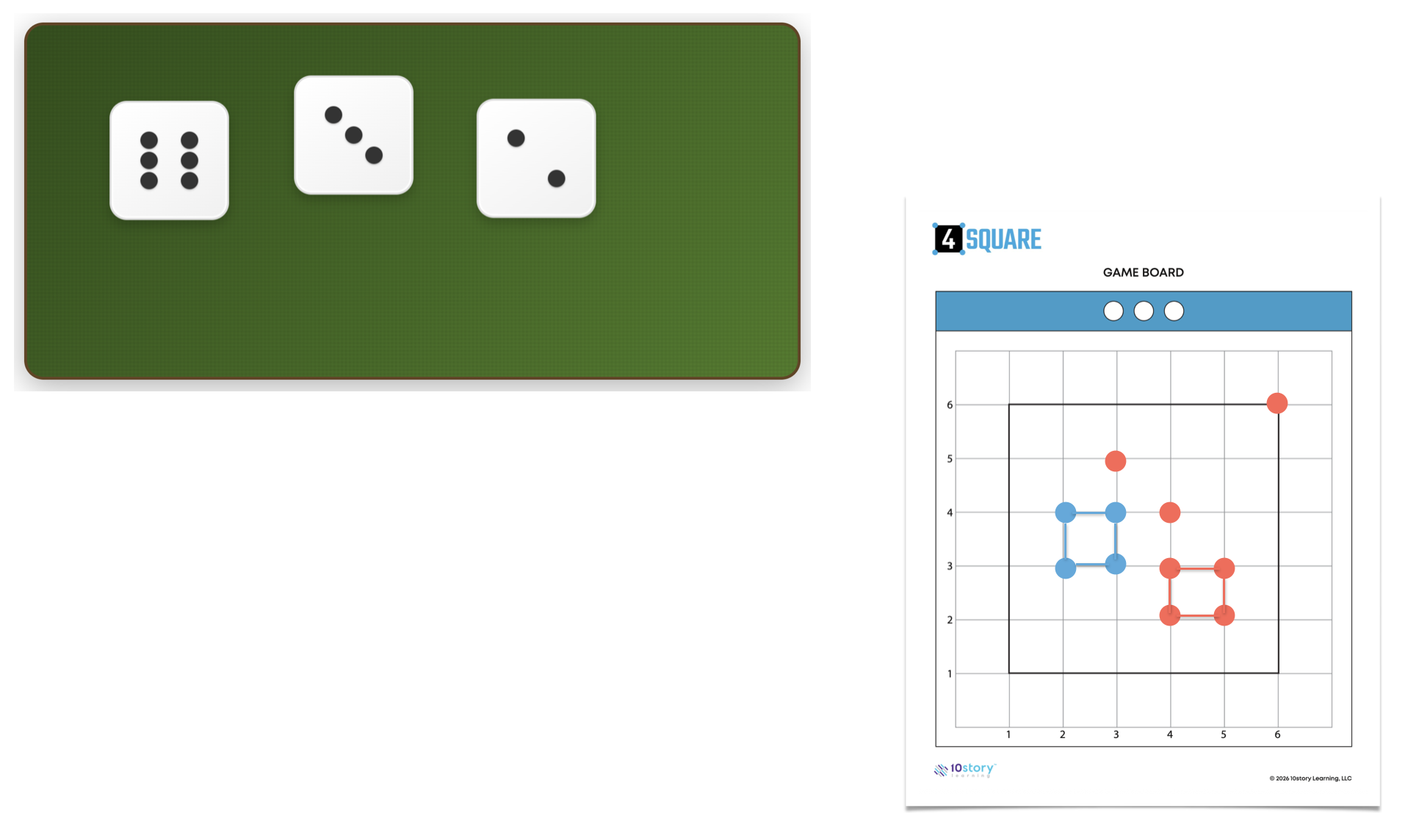

The core mechanic is simple. Roll three dice (say 2, 4, 6), pick any two to form an ordered pair, plot that point. The choice matters because some placements advance your own squares while others block your opponent. A point at (3, 4) might complete your square at corners (3, 4), (4, 4), (3, 5), (4, 5)—or it might be the only remaining corner your opponent needs to finish theirs. Students quickly internalize that (2, 5) and (5, 2) are not the same location, because plotting the wrong one might hand the game to their opponent.

Four points at (x, y), (x+1, y), (x, y+1), (x+1, y+1) form a 1 × 1 square. Students recognize these patterns visually after a few games, moving from conscious counting to intuitive recognition of "three corners present, need the fourth."

Adjacency becomes concrete: two dots are horizontally adjacent if they share a y-coordinate and differ by 1 in x. Vertically adjacent means shared x-coordinate, difference of 1 in y. Students connect adjacent dots with line segments, building partial squares. After a few turns, the grid shows a network of connected and isolated points, and students must mentally project which combinations could become complete squares given their remaining dice possibilities.

The three circle trackers end the game when filled. If you roll combinations that are all occupied, you fill a circle instead of plotting. This happens more as the grid fills—a simple introduction to changing probability based on remaining outcomes. The trackers prevent the endgame from degenerating into frustrated rolling when most coordinates are taken.

The competitive structure does the pedagogical work. Students aren't plotting points because the worksheet says to—they're plotting because they need that corner or because blocking that coordinate wins the game. The coordinate plane stops being an abstract representation system and becomes a tool for spatial problem-solving. When a student plots (5, 3) to block an opponent's square, they're using coordinate geometry for strategic thinking, which is conceptually similar to how coordinates function in mapping, computer graphics, or any other applied context.